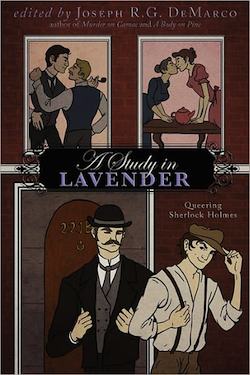

A Study in Lavender, edited by Joseph DeMarco, is a 2011 anthology from Lethe Press that features a variety of queer-themed stories set in the Sherlock Holmes canon(s); some are (obviously) about Holmes and Watson’s relationship, but others deal with characters like Lestrade or focus on cases that involve queer folks. It’s a neat project featuring predominantly early-to-mid-career writers, some who regularly write queer fiction, some who write romance, and some of whom are more familiar to speculative fiction readers—Rajan Khanna, Lyn C. A. Gardner, Michael G. Cornelius, and Elka Cloke, for example.

Scholars and fans have been arguing about the implications of queerness in the Holmes canon for a long time—it’s a popular topic. Two men in an intense emotional relationship, living together, sharing spaces and finances and their lives; well. It’s suggestive, and it’s intriguing. Both of the most recent big-name interpretations of the Holmes stories—the Robert Downey, Jr. movie and the BBC’s delightful Sherlock—have played with the intensity of the relationship between Holmes and Watson, explored it and made suggestions about it.

This book seeks to do the same, but much more openly, as well as exploring the possibilities of other queer folks whose lives may have intersected that of the Great Detective.

The Holmes fandom was one of my earliest nerdy interests as a young reader, and it’s something I still have warm feelings for, so when this book was announced I was thrilled. My expectations were fairly high; Lethe Press’s books tend to be enjoyable, and there was little that could go wrong with a book subtitled “Queering Sherlock Holmes.”

I enjoyed A Study in Lavender quite a bit, though there are ups and downs in story-quality; some are attention-grabbers, well-written and engaging throughout, several are good but have minor flaws, and one or two didn’t click with me as a reader in the slightest. I found it especially interesting to see writers from so many different fields coming together in a single anthology and to appreciate what sensibilities each of them bring to their particular tales. It’s a very playful book.

The stories:

“The Adventure of the Bloody Coins” by Stephen Osborne—This is the first story and unfortunately my least favorite; overdramatized and clumsy, at best. I was unconvinced by Osborne’s characterizations. It could have been a potentially interesting tale about Mycroft’s relationship to his brother and his sexuality, but instead it’s a bit farce-like, with overflowing emotions everywhere and no real connection to it on part of the reader or even the characters themselves. As I said, my least favorite of the volume, but it gets better from here.

“The Case of the Wounded Heart” by Rajan Khanna—Khanna’s contribution is a story about Lestrade that only lightly touches on Holmes; the inspector’s caught up in a potential scandal of his own and has to handle it himself, without involving the other man. The tension in this story between Lestrade’s career, his desires, the law and his feelings for Holmes is well-handled—the mystery isn’t necessarily the central focus, but rather the catalyst that allows an exploration of the characters. The prose is polished and effective.

“The Kidnapping of Alice Braddon” by Katie Raynes—The contributor’s notes say that this is Raynes’ first publication, which surprises and pleases me, because this was one of my favorite stories in the collection. I wouldn’t have guessed that she was a beginner from the story; it’s subtle and lovely, with a good mystery and an even better examination of the relationship between Holmes and Watson (whatever that may be). The story takes place after Watson has returned to live with Holmes, post-Mary’s death and Holmes’ pretending to die, and deals quite deftly with the negotiations of resuming a close emotional relationship in the wake of what could be perceived as a few betrayals on each side. This is all woven through the mysterious “kidnapping” of a young woman, who is actually a lesbian trying to escape her family to be with the woman she loves—mythic references and Sapphic poetry abound. Additionally, Raynes has done a fine job working within the Holmes canon and using references from the original stories themselves in a way few of the other contributors do.

“Court of Honor” by J. R. Campbell— “Court of Honor” is one of the darker tales, a quickly paced story of justice meted out by Holmes and Watson against a group of men who arranged the suicide of an old classmate they found out was gay. It focuses a bit more on the social pressures of Victorian London and less on the potential relationship between Holmes and Watson, though they are certainly in agreement about getting justice for the murdered man.

“The Well-Educated Young Man” by William P. Coleman—Coleman’s contribution is a short novella, another favorite of mine from this collection. It’s in the traditional Doyle style—”written” by Watson for posterity—and explores the tale of a young gay man who finds his way into Holmes and Watson’s life, at first just for a chat and then for a case about his missing lover. It’s one of the most historical pieces, using terminology of the time and referencing Havelock Ellis’s work on “sexual inversion” in a few places.

The story moves slowly, and there’s much more going on than simply the mystery, but that’s not necessarily a bad thing. The writing was concise and pleasant enough that even the asides and speculations on Watson’s part about the law, about sexuality, and about writing all fit in quit well. This story, like several others, explores the intricacies of the relationship between Holmes and Watson—but this time from the point of view of a heterosexual Watson who nonetheless loves Holmes quite deeply and is surprised to work out, during the case, that Holmes himself is gay. Much of the story is about subtly changing Watson’s mind about “inverts” and his halting understanding of the kind of life his closest friend must have had to lead under the restrictive and frightening laws of the time. It’s an emotionally intense story, not just because of the densely woven relationship between Holmes and Watson but also because of the realistic portrayals of the dangers of gay life in the Victorian era. It’s one of those stories that reminds a queer reader that it hasn’t been so long since those laws were on the books and sends a chill down one’s spine because of it.

“The Bride and the Bachelors” by Vincent Kovar—Kovar’s tale is a story from Sherlock’s point of view, as he and Watson settle the case of a missing groom, who it turns out would much rather be a bride. The original bride is all right with that; arrangements are made for her to live with the happy couple in France, so each can get what they need most from the relationship: George gets to be Georgina with her lover, and the original bride gets a comfortable, happy life abroad with her “husband,” who is much more a friend. It’s a story that I want to have liked, and in some ways I do, but the writing was clumsy—accidental repetitions, misused words and the like. The end feels a bit rushed, too, though it is cute in its way, a happily ever after for Holmes and Watson (who discover they would like to be “confirmed bachelors” together after all) and the trio involved in the case.

“The Adventure of the Hidden Lane” by Lyn C. A. Gardner—Gardner takes another angle on Holmes’s identity in her story; he’s asexual, by choice in this scenario, or so it seems from the dialogue. I was surprised not to see more exploration of this possibility in the collection, as it’s one of the biggest scholarly suppositions about Holmes—that his relationship to Watson was intensely emotional, but that he himself was asexual and therefore there was no physical relationship (hence Watson’s wives). It’s a melancholy story, ending on a sharp note, and for that I enjoyed it. I’m not always looking for happy endings. The mystery in the tale is serviceable if not remarkably easy to figure out from nearly the first moment, but the real climax is the last page and the conversation between Holmes and Watson that marks, as Watson says, “In the very moment I recognized our golden age, I knew that it was over.” It’s quite the strong blow to the reader. (One minor complaint: a few too many commas.)

“Whom God Destroys” by Ruth Sims—”Whom God Destroys” is set in the “real” world, with Arthur Conan Doyle as a side-character and the serial-killer narrator rather a fan of Sherlock Holmes when the stories are first published in The Strand. The writing is fine, but I find the serial-killer-as-narrator trick is hard to pull off, and I don’t think Sims quite succeeds. Additionally, there’s the “killer transvestite” angle that raises my hackles—it doesn’t outright say anything nasty, but I’ve seen a few too many stories and movies about the “crazed gay man in a dress” who goes about murdering people; it’s just not on, especially because there are several hints in this story that Sebastian/Angelique begins to consider herself as, well, herself, making it into that other stereotyped story, the “killer crazy transsexual/transgender woman.” The story itself may have nothing outwardly transphobic in it, but there’s a pretty unpleasant lineage of stories that it fits into that make me uncomfortable as a reader and critic. That likely was not the author’s intention, but it has ugly resonances all the same.

“The Adventure of the Unidentified Flying Object” by Michael G. Cornelius—Cornelius’ story has queer content mostly in hints and subtext, much like the original Doyle stories; unless the reader is aware of the context of the “club” that Holmes is a member of, it’s hard to put the pieces together. Again, much like the original stories. It’s a deftly written little story with science, deduction and a little joke about Verne mixed in, plus a delicious hint about Moriarty. I enjoy that this story is set pre-most of the Holmes canon; it gives a different vibe. This is perhaps the most fun of the stories in the book, and the one most likely to tickle your fancy to imagine what might come later, when Watson is “ready” to learn what that club is all about.

“The Adventure of the Poesy Ring” by Elka Cloke—The final story in the volume is another mystery concerning a gay couple that prompts a change in the relationship between Holmes and Watson, and this time the case is a murder. This story is one of only in which Watson makes the first move, initiating the single kiss that’s shown to the reader, and we’re never quite sure if it happens again. This story, too, has hints of Holmes’ potential asexuality, though it’s left an open question in the end. I enjoyed the tale; it’s a touching ending to the collection with nicely memorable last lines to close out the whole thing: “Is it any wonder that I followed him at a moment’s notice, anywhere in the world? I always have done so, I do so now, and I always will.”

A Study in Lavender: Queering Sherlock Holmes is good light reading—fun, with several good stories, and enjoyable for the play with literature and the Sherlock Holmes canon inherent in its subject matter. Its flaws are its occasional faulty editing and one or two flat, clumsily written stories.

A Study in Lavender: Queering Sherlock Holmes is good light reading—fun, with several good stories, and enjoyable for the play with literature and the Sherlock Holmes canon inherent in its subject matter. Its flaws are its occasional faulty editing and one or two flat, clumsily written stories.

I’m glad that Lethe Press published the book and that editor DeMarco put it together; it’s a good read and a worthwhile project. For fans of queering classic literature and/or fans of exploring the possibilities of the relationship between Holmes and Watson, it’s certainly something to pick up.

[This article originally appeared in July of 2011]

Lee Mandelo is a multi-fandom geek with a special love for comics and queer literature. She can be found on Twitter and Livejournal.

Oh goody, I remember hearing about this book before and was interested in it, glad to see that it holds up and I’ll have to try and find a copy for myeslf!

I totally missed this the first time round, so thanks for reprinting! Off to buy myself a Kwanzaa gift.

Definitely an interesting prospect – thanks for the review, and the re-post thereof. :)

I think it’s interesting how we’re not really able to conceive of a strong platonic relationship between two people of the same sex without pretty much immediately thinking, “gay”.

@Syllabus: I never thought or think of them as gay (or asexual or what-have-you), but for me it’s more like indulging in fan-fic. It’s a neat and entertaining way of exploring a new take on a classic. I think anyone who spends all their time analyzing the psychology of fictional characters goes above and beyond the author’s intent and it’s ultimately meaningless, but that doesn’t mean you can’t enjoy the hell out of picturing Benedict Cumberbatch and Martin Freeman spending a little quality time alone together.

@Milo1313

Well, yeah. What people write about in their fan fiction is their own affair. What I’m talking about is how some people – including some friends of mine – seem to leap automatically at these sorts of situations, in literature and real life, from that angle. Now, from the angle of the BBC’s new Sherlock, that sort of joke makes a bit of sense, as it’s intended to be a contemporary re-imagining of the Holmesian mythos. And I do enjoy that series greatly. Freeman is, to my mind, the truest Watson since the Jeremy Brett series. And, nowadays, one might very well think that two bachelors in that situation might be batting for the other team.

But take A Game Of Shadows, for instance. Granted, it’s not quite within a hundred miles of the original Holmes and Watson characters, but it’s still damned entertaining. However, they really do play up the homoerotic overtones between the two of them (while it was more of a bromance in the first film). It’s quite funny, no doubt, but it’s a little out of place in the setting of Victorian England.

That’s actually another quibble I have with the Ritchie films. Holmes is supposed to be asexual in the extreme, which makes his “relationship” with Adler all the more annoying to Holmes purists (like myself).

If someone chooses to write a fan fiction from that angle, then they have every freedom to do so. I am, however, left sorely bemused at this sort of projection onto the original literature. You know what assumptions do to you and me, after all.

I know, I know, I’m an incurable pedant. That’s just how I roll. :)

Syllabus @6: Don’t worry too much about pedantry: after all, it’s the heart of geekiness on the Internet.

But I don’t think that an anthology like this is a “projection onto the original literature”, any more than Neil Gaiman’s “A Study in Emerald” is an attempt to put Cthulhu into the Doyle canon. I feel like the characters of Holmes and Watson have metamorphosed into archetypes. They’ve gone beyond the original Doyle stories and into the collective unconscious of our culture as something else (in a way similar to James T. Kirk, Batman, and arguably even Jesus). Holmes and Watson no longer belong to Arthur Conan Doyle*. They belong to all of us.

If you like, you can think of the characters in A Study in Lavender as aspects of some platonic Holmes and Watson**– who just happen to be gay.

(*Note that this concept of “belonging to all of us” has nothing to do with copyright and public domain. It’s something deeper, and more Jungian.)

(**Also note that the term “platonic Holmes and Watson” aren’t Doyle’s Holmes and Watson. They are something else, beings which cast many shadows, each of which we perceive in our own way.)

@Milo1313

Do my eyes deceive me? Have we a Jungian here on the internet, the last and strongest redoubt of the Freudians with their Rule 34, phallic jokes and infantile double entendres? I metaphorically shake your hand, dear sir/madam.

And as far as the Holmes canon goes, there is something to be said for reimagining, I suppose. And tastes in literature are largely subjective (except where the paragon of inane linguistic incompetence that is Stephanie Meyer is concerned – that’s just plain bloody awful), so I can understand why some people would find that sort of thing entertaining. In Gaiman’s adaptation, though, the characters retained their basic forms, though in a different setting. Moriarty and the other doctor were on the side of the “law” – in this case the Great Old Ones or whichever Lovecraftian horrors they actually were -, while Holmes and Watson were on the side of “anarchy” – which in that particular case is arguably the side of the “good guys”, such as there would be in that scenario. Different settings, but the characters remain more or less unchanged.

That’s the thing that sort of bugs me about adaptations of books to film or reimaginings of that book: the characters almost always feel different (with the notable exception of the excellent Game of Thrones show). Take Faramir in Jackson’s LOTR films, for example. The character was rather drastically changed in the second film, in a way that was irksome to me. He didn’t quite seem like Faramir until the very end of that film, and even then he was a bit of a pale reflection of the original book’s character. To me, at least.

As far as the platonism is concerned, I meant it only insofar as to indicate the lack of a romantic or erotic undertone to their relationship. The friendship between the two of them is, no doubt, much stronger and deeper than may seem apparent at first reading.

So, all that to say, pretty much the only thing that I don’t quite get is the passion people have for reinventing the characters in such a way as to change them completely. If you’re going to have a gay character, fine. Flesh him/her out from the beginning, and be consistent about it. But changing an already well-known character that much seems a little gimmicky to me. It’s like what that insipid Ultimate Universe line of Marvel Comics did to Colossus. In 616, he’s straight, and that is a huge part of his character, what with his on again, off again thing with Shadowcat, etc. In the Ultimate line, he is (was? I no longer read that line) gay and together with Northstar, if I recall correctly. Which, as far as a literary character goes, would be fine with me if 1). it wasn’t so poorly written and 2). it didn’t feel as ad hoc as it does there. If they were trying to give the character a different feel, they certainly succeeded, but doubtless not in the way that they intended. I wish that entire universe would go away and never come back (gollumgollum). A bit like that whole Brand New Day business; I still sometimes curse Quesada’s name under my breath and beesech whichever gods govern the comics world that JMS gets to do Spiderman yet again before he or I dropkicks the bucket.

As far as them being archetypes, you might be on to something there. It’s the sort of “bosom buddies” thing that you see echoed in literature from Don Quixote to, I don’t know, Calvin and Hobbes. I would venture to say, though, that if they are a manifestation of an archetype, they are a manifestation of a pre-existing one rather than one that is wholly new. Alas, I am not a trained psychotherapist, and thus know not what service to integration this ideal does. Nor am I informed enough to theorize with much success – though I could spout off conjecture till the Second Coming and still not be done with, or even coherent on, this point.

So it just feels… weird, I guess. Everyone’s entitled to their peculiarities and oddities. After all, some people dress up as furries, for Heaven’s sake. Takes all types. Late night internet posting not being an activity that lends towards either clarity or brevity, I shall leave it at that.

Syllabus @8:

Heh. I’m hardly a Jungian, although I do think that there is something to be said for Jung’s theories. More than can be said for Freud’s theories– Sigmund Freud always struck me as a sad, sexually frustrated old Wiener.

(Yes, that was both a phallic joke and an infantile double entendre. But it’s a double entendre that happens to only make sense with a passing knowledge of German, so that makes it all better, doesn’t it?)

Anyway, that’s one of the things I love about stories. Stories can mean such different things to so many people. They’re a fascinating interaction between the teller, the listener, and the story itself.

(And, because we really can’t bring up Gay Holmes without mentioning Kate Beaton… behold: http://harkavagrant.com/index.php?id=264.)

My chief annoyance with this collection is that it could do with a really good historical Britpick. Or even a completely basic one.

They didn’t have “pound coins” in the 19th century (“sovereigns”, please), which completely ruins the plot of the first story, for instance.

Oh, and Syllabus, if you think having homoerotic subtext makes it somehow less ‘Victorian’, I think you need to bone up on your 19th century history as well. Not that I rate the Ritchie movies in the slightest: can’t abide them.